Financing Care is Financing the Future

A Feminist Call from Southern Africa to Fourth Financing for Development Conference (FFD4) in Seville, Spain.

From the Economic Justice Desk of The Southern Africa Trust (The Trust)

As the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD4) convenes in Seville, Spain, from June 30-July 3 2025, The Southern Africa Trust (The Trust) calls on governments, international financial institutions, donors, and private sector actors to take five bold actions:

- Re-centre care work in development planning and public financing frameworks.

- Raise and spend domestic resources in gender-just, care-oriented ways.

- Link debt relief to binding commitments for social spending, especially care.

- Embed care in climate and crisis financing instruments.

- Fund and scale feminist, community-led models of care.

These actions are not optional. They are preconditions for inclusive development, economic justice, and gender equality. The time for rhetoric is over. FFD4 must deliver concrete resources to the care economy which is the backbone of society.

The Political Economy of Care

As global leaders gather for FFD4, one truth is glaring: the chronic underinvestment in care work is undermining Africa’s development. Care is not a side issue it’s a political, economic, and moral crisis. Across the world, women perform three times more unpaid care and domestic work than men, yet this immense labour remains mostly invisible and undervalued in traditional measures like GDP. Because care work is overwhelmingly feminised and often racialised falling to low-income women in marginalised communities it is consistently devalued and deprioritized by policymakers. According to APEC (2022), if monetised, unpaid care could equal 9% of global GDP about $11 trillion. And yet, it remains a blind spot in fiscal frameworks, national budgets, debt negotiations, and stimulus plans.

Ignoring the care economy is a profound structural failure. Care is the social infrastructure that makes all other work possible. It sustains families, health systems, and human capital formation. When this foundation is neglected, development rests on shaky ground. The impacts are evident in Africa today: women’s labour force participation and productivity are constrained by unpaid care burdens, and gender inequalities are reinforced as girls and women sacrifice education and formal employment to fill care gaps. If FFD4 is to be remembered as a turning point, financing care must move from the footnotes to the frontlines of the development agenda.

What the Evidence Tells Us: Lived Realities of Care in Southern Africa

In 2025, the Southern Africa Trust conducted a Feminist Analysis of the Care Economy across five SADC countries (Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, and South Africa) combining feminist political economy research with community consultations, public finance reviews, and interviews with frontline care workers. The findings paint a visceral picture of how under-financing of care is letting down women and girls:

- Colossal Unpaid Work Burdens: Rural women commonly spend 60% of their working hours on unpaid care tasks, with daily totals reaching 14–16 hours. This leaves them exhausted, time-poor, and unable to engage in paid work or civic life.

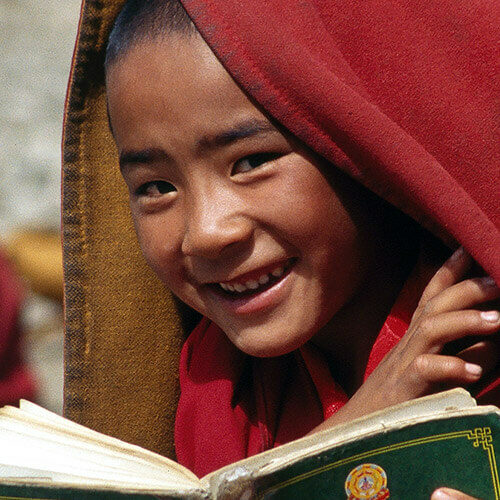

- Girls Sacrificing Education for Care: Girls as young as 10 are dropping out of school to care for relatives, manage households, and plug the gaps in public support systems. Their right to education and childhood is compromised by assumptions that families meaning women and girls will simply “cope.”

- Negligible Public Investment in Care: Most governments offer almost no public childcare, eldercare, or community-based care. National budgets treat care as a private matter, not a public good, leaving women to shoulder it alone.

- Underpaid, Informal Care Workforce: Paid care roles like domestic work and community health are typically informal, low-wage, and lack protections. Over 90% of African women in low-income countries work in informal care roles without rights or security.

- Crisis Intensifies Care Responsibilities: Droughts, pandemics, and austerity cutbacks worsen the burden. Women absorb the fallout walking further for water, nursing the ill, and managing food insecurity all without compensation or support.

These realities reveal one truth: care is the invisible engine of development. And it is sputtering under unsustainable strain.

Why Financing Care Is a Development Imperative

It is time to move beyond seeing care as a private issue. Care is core economic infrastructure. Investing in robust care systems has wide development benefits:

- Job Creation & Economic Growth: Care investments generate 2–3 times more jobs per dollar than infrastructure sectors and are greener. Globally, nearly 300 million jobs could be created by 2035 through care investments 78% of which would go to women.

- Boosting Women’s Participation & Productivity: Lack of care services limits women’s ability to work. Universal childcare can raise women’s workforce participation by 10–15%. Pilot programs in Africa show higher retention and income for mothers when care services are available.

- Combating Time Poverty & Improving Human Development: Reducing drudgery (like fetching water or cooking over wood fires) through clean energy, healthcare, and childcare investments gives women back critical time. This improves mental health, increases participation, and benefits whole communities.

Across crises, African women’s unpaid labour has propped up broken systems at incalculable personal and societal cost. The return on investing in care is massive. Financing care is smart economics it expands the labour force, grows GDP, and improves human well-being.

The Structural Roots of the Financing Failure

If care investment brings such gains, why is it neglected? The problem is structural, rooted in four interlocking financing failures:

- National Budgets Treat Care as Private: Public budgets overlook care as a societal responsibility. Even where constitutions commit to gender equality, care is underfunded while militaries and debt service get priority.

- Debt Burdens Crowd Out Social Spending: Countries like Zambia and Mozambique pay more on debt than healthcare or education. Austerity forces women to absorb the shortfall by providing unpaid care.

- Regressive Tax Systems Undermine Equity: Heavy Value Added Tax burdens fall on poor women, while corporate wealth is under-taxed. Budgets remain gender-blind, ignoring the care burden and widening inequality.

- Global Aid and Climate Finance Ignore Care: International aid focuses on hard infrastructure. Climate finance often overlooks women’s unpaid work, missing opportunities to fund water, cooking, and care infrastructure that directly reduce women’s workloads.

The result? Governments and donors systematically fail African women and girls by rendering their care work invisible.

Care is Political, Not Just Personal

The hours women spend daily caring for others are an unacknowledged economic subsidy. These hours make economies function and societies thrive. Yet for too long, this labour has been treated as elastic, infinite, and free. Every macroeconomic policy has a microeconomic face often that of a tired woman in a rural village or an overburdened girl in an informal settlement. If Africa is to prosper, it cannot do so on the backs of exhausted women and denied girls. We must invert the narrative: women should not be made more “resilient” our systems must be. As we reach the midpoint to 2030 and reflect on 30 years since the Beijing Women’s Conference, Southern Africa has a clear message: Financing care is financing the future. The unpaid labour of women has held up broken systems long enough. Now the systems must hold up women.

FFD4 can be the turning point. It’s time to act: to finance care, and in doing so, to finance a more just, equal, and thriving Africa.